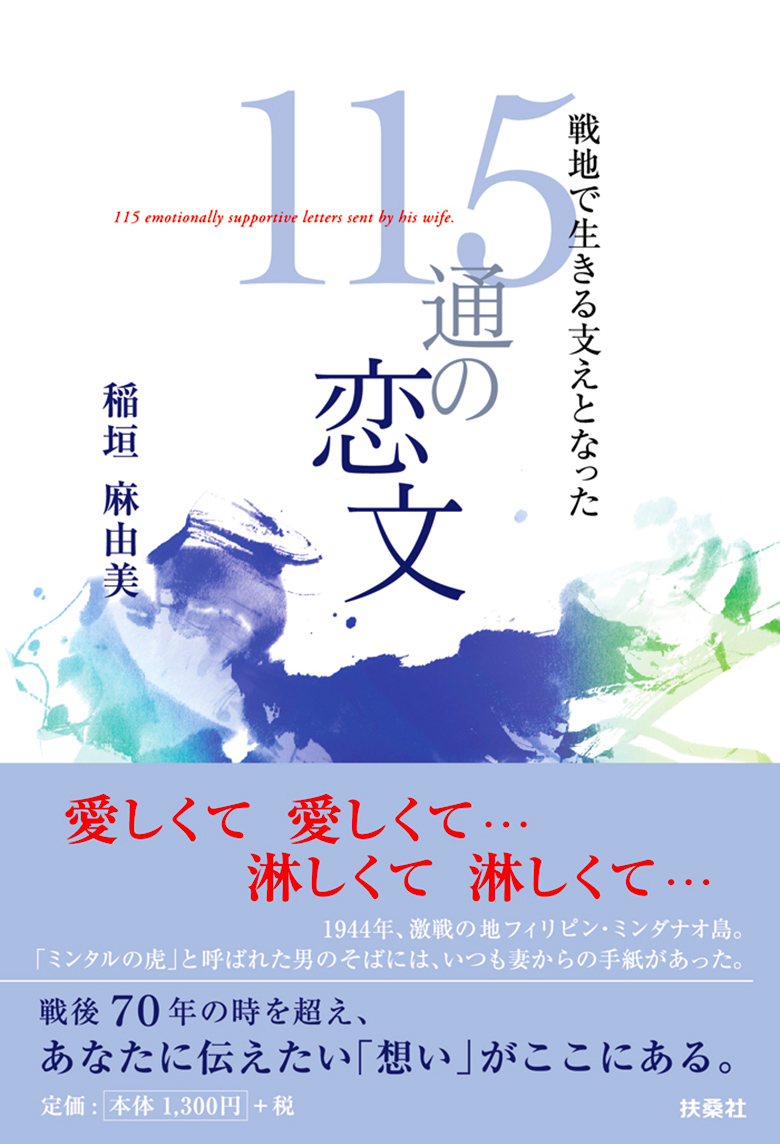

115 love letters - sustenance in the battlefield

Around the time when the Sino-Japanese War was developing into the Pacific War, one woman frequently sent letters to her husband in the battlefield. Of those letters, 115 exist to this day. At that time the woman, pregnant with her first child, was missing her husband desperately—him being so far away in such perilous circumstances. She wrote to him of her love for him, her anxiety and loneliness—these evocative and poignant letters will touch every heart, beyond time and borders.

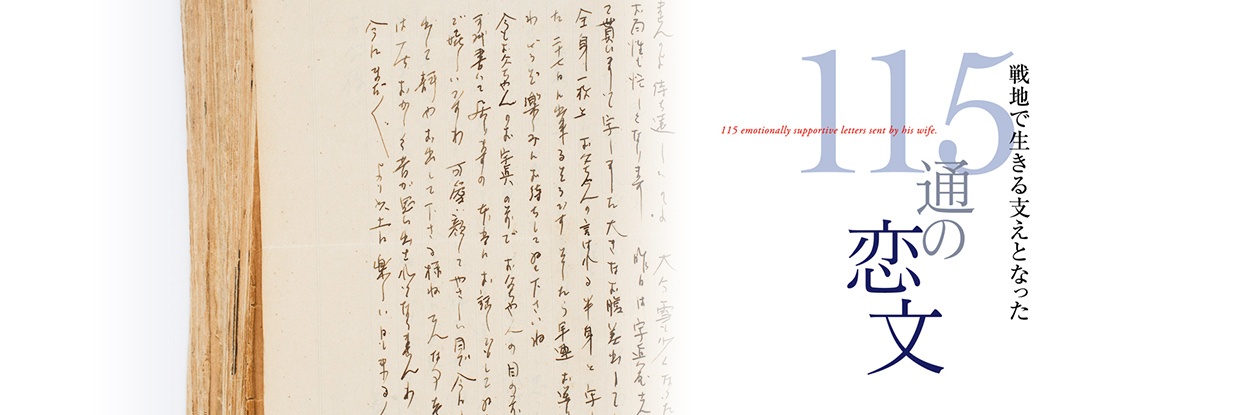

My dearest husband,

Please remember that everybody, God, the Buddha, your parents, and I, everybody is always protecting you. I assure you that I am fine with my big tummy, and I am disciplining my spirit every day. Soon it will be nine months. You will be surprised to see how big my tummy's gotten. Lately I cry easily about every little thing. I know I cannot live without you, so please, please stay alive, come back home alive...

My darling husband,

I am so lonely. So lonely that I put on your clothes just to feel close to you. I was remembering the days when you were wearing these clothes. I was filled with emotion...

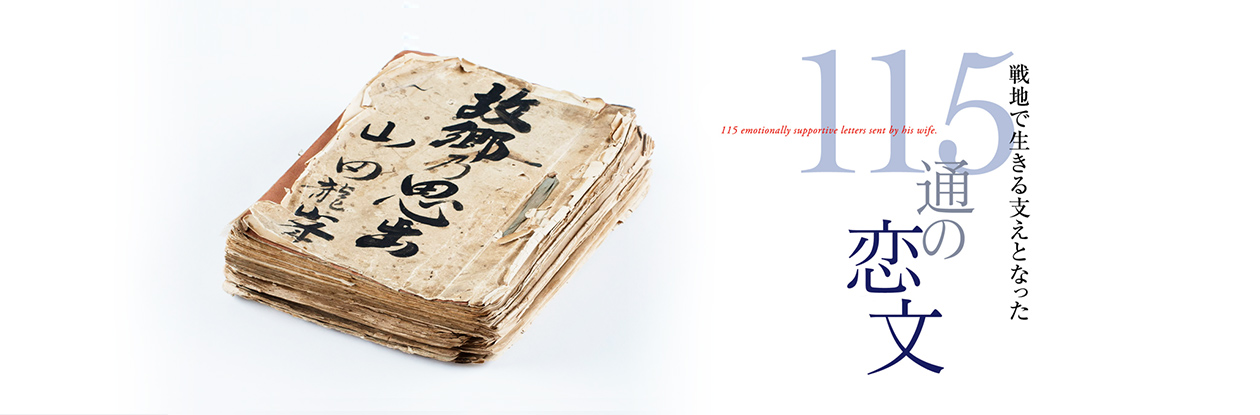

Although greatly pained by her loneliness, it seems that she set her mind to be strong, as the wife of a military man should be. Even now, 80 years later, we can feel her complicated state of mind as we read her handwriting in those yellowing, crumbling letters.

The husband, Fujie Yamada (born in 1907), was the sixth son of a farmer. At the age of 21 he was drafted into the infantry as a private. With his excellent reflexes and good physical condition, he distinguished himself and entered the military academy at age of 29. Later, he was called the “Tiger of Mintal” because of his performance on the battlefield. When the war finally ended he was a major, and was the battalion commander of the 353rd independent infantry battalion on the island of Mindanao in the Philippines. After being held in a prison camp in Davao for a year, he returned to his hometown in Fukui Prefecture in Japan in the autumn of 1946.

The wife, Shizue Yamada (born in 1913) was also from Fukui. They married when she was 23. After the war she raised their six children and supported her poor family by doing needlework.

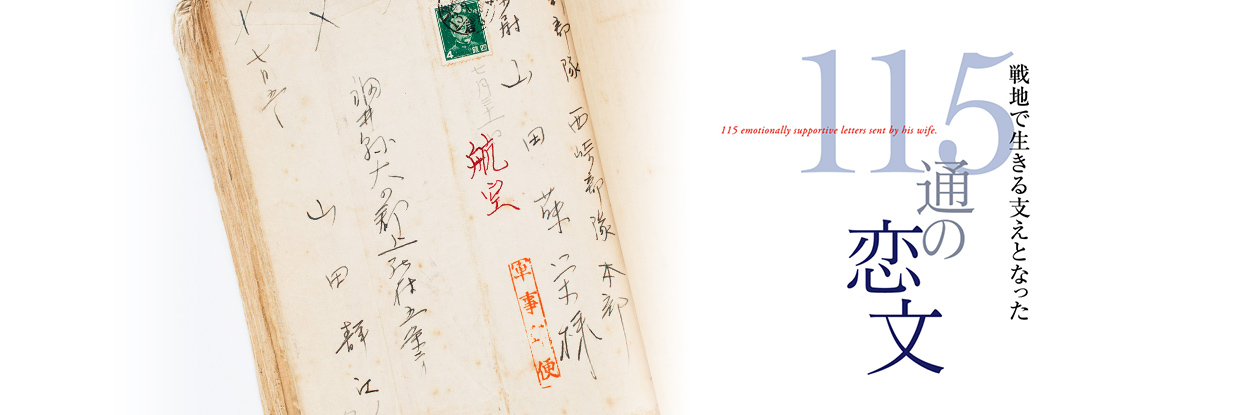

Shizue and Fujie were separated just after their marriage, and were apart for two years during the early part of the war. These 115 letters are the ones she wrote to him during that period. Fujie wrote the date on each letter when he received it, and he kept all her letters and envelopes in a bundle tied with string. Their exchange of letters ended the moment he came home; soon after the family moved together to Manchuria.

Then in 1944 Fujie was ordered to fight in the south. It seems he took the old love letters from their newly-married days with him, because when he came back home again in 1946 there were 115 letters in his backpack. Their first daughter, Kikuyo Yamada (now Mrs. Watanabe), who was eight years old then, clearly remembers the scene of his return home. Inside her father’s backpack there was only some sugar candy, some raisins and the bundle of letters. She wondered what they were. She never forgot the image: the letters, the vivid orange color of the persimmons in the garden, and her father’s emaciated body.

The southern battle line where Fujie was dispatched in 1944 was a harsh battlefront; everyone faced extreme starvation and infectious diseases. Many solders suffered from malaria and amoebic dysentery, and 90% of them died of starvation. Those soldiers who managed to survive had no other choice but to escape to the mountains and feed themselves during the long drawn-out battle. It was said that was the epitome of that horrible war. 498,000 Japanese solders died in battle in the Philippines. Some records indicate that the Japanese death toll, including Japanese who originally lived in the region, reached 510,000. There were 1,152 men in the Yamada troop led by Fujie: 967 of them died—only 165 survived.

After the war, Fujie never talked about his time in the battlefield. The only exception was in Shizuoka in 1974, when he made the opening speech at the ceremony for a new cenotaph for the Yamada troop. Fujie died at age 90 but he had suffered from dementia from the age of 80. For ten years he roamed the local shrines and temples and collected objects such as pebbles, dead birds and human waste to take home. His family said that it was as if he were collecting the remains of his soldiers who had died in the Philippines. This is another negative side of war: that people have to live keeping secrets that they cannot share with anyone. In his extreme mental state during the war, Fujie must have gotten great support from those love letters. When we look at his later life, we can easily imagine that.

In these letters, which miraculously survived for over 80 years, there are words and thoughts that should be heard by modern people. The messages contained in these love letters will surely move us and make us think deeply about life and love, war and peace.

To inquire about the letters or the book, please contact here.

いつの世も、愛する人を思う切ない気持ちは変わりません。

まして、明日の命をもしれぬ戦時下においては、その思いはより切なく、より特別なものとなったことでしょう。

時代が日中戦争から太平洋戦争へと向かう頃、戦地の夫へ手紙を送り続けた妻がいました。まだ結婚して間もなかった二人には、その別れはつらく、妻のお腹には初めての子が宿っていました。今ではすっかりセピア色に、いえ、深い黄褐色に変色した便せんに綴られた手紙には「淋しくて、淋しくて」と書かれた妻の文字……。

戦地にいた夫は、その手紙が届くたびに、いつ届いたのか日付を記し、番号を打ち、封筒もきれいに開いて、麻の布地を細く切ったようなひもで綴じ始めました。その数115通。当時、部隊は日々移動するため、宛先は「中支派遣 藤江部隊気付 南部部隊 木村部隊本部 歩兵中尉 山田藤栄様」というように、いわゆる住所ではなく所属する部隊名でした。

私がこの手紙と最初に出逢ったのは2009年のこと。私のいわば「鎌倉の母」ともいうべき、料理研究家の渡辺喜久代さんから「実はね、あなたに見せたいものがあるの」と、手渡されたのがこの115通の恋文でした。訊けばこの手紙は、陸軍軍人であった喜久代さんのお父様と、お母様が戦時下に交わしたものだというではありませんか。驚きました。何と言っても、この手紙は70年以上も前に綴られたものなのです。

この手紙には、「愛しい」「恋しい」との言葉が頻繁にでてきます。私は大正生まれの女性が「愛しいあなたに抱かれたい」と素直に書いていることにまずは驚き、「安心」という言葉を「安神」と書かれていたことに驚きました。

戦争を知らない世代の私が何かを偉そうに伝えることはできません。ただ、この手紙を通して、この時代に思いを馳せ、何かを感じ取っていただければ何より幸いです。

戦後70年を迎えた今、伝えたい「言葉」と「想い」がここにあります。